This post was written with Ethan Lowenstein, Director of the Southeast Michigan Stewardship Coalition (SEMI’s). SEMI’s does tremendous work in the development of an educational approach that values, among other things, place and responsible citizenship, grounded in an ethic of Ecojustice. Check them out here.

Chet Bowers asks a question that we should all be considering, especially those of us who serve as educators: “How do we live more interdependent lives based on practices that are less dependent on a monetized world, that are less environmentally destructive?”

So what exactly does such a question have to do with education? Aren’t we supposed to help kids get into college?

Sure. Of course.

But usually the unspoken purpose of getting kids into college is to help them find a nice paying job that allows them to live independently as opposed to interdependently. It allows them to find a nice paying job because of the need to do so in a monetized world. That is, “achievement” is synonymous with “success,” which, in today’s market driven world is synonymous with making a lot of money, of having a “good job,” of acquiring the means to acquire endlessly. And, needless to say, this alienated individualism- the self as separate from relationship and responsibility to community- leads to a consumerism that certainly exacerbates environmental destruction. It seems our current story too often takes us in the opposite direction from that which Bowers’ question is pointing us towards.

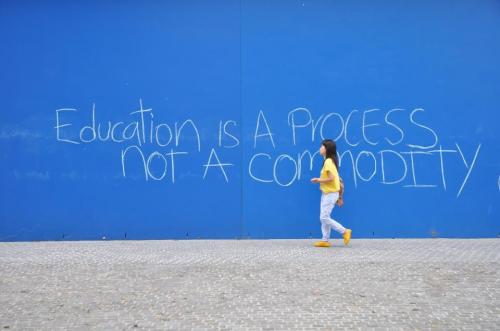

We propose a different purpose of education, one that is rooted in practices that reveal our interdependence to each other and to our environment, and that promotes the value of community over the single dimension of the market.

The Problem With Hierarchy

Before we get to the vision, it is important to name the obstacles to such a vision, obstacles that can be deeply hidden. These obstacles are tied to what Bowers calls our “root metaphors,” language metaphors that limit what we see and speak. We argue that at the foundation of these root metaphors is the notion of hierarchy.

Hierarchy is a particular way of imagining human organizations, and as such, represents a particular means of organizing power. Hierarchy embeds power within a structure that coalesces it from “the top,” allowing access to few as a means of creating “efficiency,” and the more centralized, the more “efficient.” It works to privilege power over others, rather than power used with others. We have no issue with power. The issue is, who has power? Where does that power come from? And, importantly, what value does that power function to express?

All systems create a code, a text for communication. The ability to critically read the text of organizations is a crucial skill for all of us.

In their important book, The Abundant Community ,John McKnight and Peter Block help us read the text of hierarchical systems. As they put it, “A system life is a way of living that is not our own but one that is named by another.” They point out that what they call “systems” do the following:

- Systems are designed to create scale. Scale in turn requires consistency, control and predictability.

- Management provides the organizing structure required to produce consistency, control and predictability….management is a way of thinking about life, family, neighborhood, schools- that these can and need to be “managed.”

- The task of management and systems is to maintain control by taking uncertainty out of the future, which is essential to fulfill the promise of consistency and scale. Standards are an attempt to create predictability.

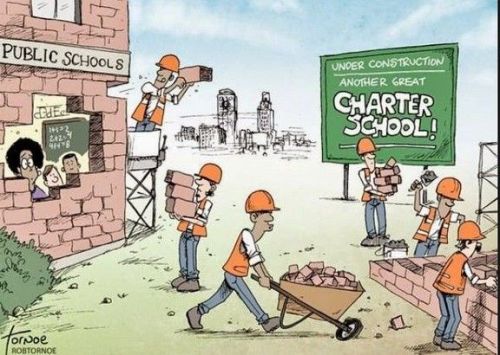

We believe these are pretty straight forward. And when applied to schools, they lead to an achievement oriented, standards-based approach. The Common Core, for instance, represents a standardized system brought to scale measured by the “accountability” (or an answering to hierarchical power) to test based measures. The task of administrators is to manage the imposition of this system. As Dr. E. Wayne Ross shows us, “Accountability is an economic interaction within hierarchical, bureaucratic systems between those who have power and those who don’t. (It is) a means of dispersing power to lower levels of hierarchical systems. Those who receive power are obligated to ‘render an account’ of accomplishing outcomes desired by those in power. Accountability schemes obfuscate identity of higher authority; serve interest of status quo/unequal power relations.” In other words, “accountability” becomes a means for those at the top to impose their will upon those under them in a hierarchical structure.

What is hidden by such hierarchical systems is the contexts that they are imposed upon. Because these systems are designed to create scale, they are also designed to erase the particularities of place and of people. Individuals are held “accountable” to the hierarchical system, and thus the unique individuality of these individuals, or of the context of place, are reduced to their roles and functions within this system. The uniqueness of who you are is sacrificed to your role function. The uniqueness of where you live is sacrificed to the the standardization required for this system to work anywhere. McKnight and Block show us that these systems suppress the personal and make human and non-human relationships utilitarian and instrumental. Individuals and communities are sacrificed in the name of scale and standards while standards create the illusion of predictability. Hierarchical systems are essential to competitive norms, of creating winners and therefore losers. They are necessary to create predictability in a world that essentializes predictability as means of “winning,” of “measuring,” of “ranking,” of “fixing,” a world that wishes to dispense with mystery, to rid itself of losing, to rid itself of fallibility. To rid itself of death.

As an example, consider a McDonald’s restaurant. A burger anywhere in the world is created to be exactly the same. A McDonald’s in China is standardized so that you can predict that a Big Mac that you buy there will be exactly the same as a burger that you buy in America. The person cooking the burger is irrelevant, as is the community that it is cooked in. A burger in a McDonald’s in America is designed to taste exactly as a burger in China.

Place doesn’t matter.

And that’s a problem.

Hierarchy allows for the abstraction from place. Hierarchy is replicable anywhere, and thus makes the context of a particular place irrelevant.

On the other hand, recognizing interdependence grounds us in a specific place. Each place has a set of relationships and living beings, who exist as ends in themselves. These beings talk to us and teach us all of the time. Accountability to them, rather than to a hierarchical system, requires learning the language of this relationship. To not learn this language is to erase these beings. It is a genocidal impulse, which, when combined with systems, leads to actual genocide. It also is a suicidal impulse, which when entrenched in an “efficient” system leads us to our own species’ suicide.

The Hope of Restorative Practices

Restorative Practices is one means of community building that offers a way into recognizing our interdependence while offering an antidote to the damaging effects of the individualized “achievement ethic.” We tend to look at schools through the ethic of achievement. Students’ purpose is to achieve success, and this success is measured by grades and test scores. This allows schools and students to be ranked according to the hierarchy of achievement that is generated. Part of the hidden curriculum in this view is that students are valued in accordance to their level of achievement. This valuing is not overt, but it is nonetheless real. And achievement becomes the means to garnering future economic success. This, again , reinforces a privatized view of student as consumer, and sees the purpose of schools as being the production of economic achievers and consumers.

The theory underlying Restorative Practices, on the other hand, is based on the use of the lens of community, rather than the competitive lens of achievement, as the view through which we see our relationships in school. This theory understands that the root of learning is the same as the foundation for being human- that is, that belonging trumps everything. This sense of belonging is a fundamental necessity in learning. If I feel that I belong, that who I am matters and is honored, then I will engage as a responsible member of this community. When I am seen and welcomed as a member of a community, I will hold myself in responsibility to that community.

Education, in this view, is not about the individual success that leads to greater “status” and an increased income and ability to consume- a privatized version of “success” which functions to create the illusion of independence and thus distances us from the necessity of the context of community. It is not about a form of learning that keeps “private” our true dependence on one another and on community. This illusion imagines power as the means of providing happiness. That is, it imagines that happiness comes with power over others, and with the power to attain “more” (more money, more status, more things, more, more, more….) Both of these forms of power lead to a dead end in terms of happiness as they are organized in such a way that they provide a privatized version of security for some, while this privatization insures insecurity for others. These forms create winners and losers, and accept a competitive narrative of what it means to be human. They create the 1% and the 99%. And ask around, few are truly happy when embedded in such a system.

Restorative Practices, on the other hand, correctly imagines students as being dependent upon the nexus of relationships that occur within the context of school. It imagines that, rather than being a pathway out of community and abstracted from place, the purpose of education is to build and strengthen the social capital of community. It recognizes that satisfying happiness can only come with Belonging. These practices explicate and leverage the necessity of our interdependence with the people involved in our community, and thus require us to learn the skills needed to function within the communities we live within.

And all of this is crucially important.

But it doesn’t address what we mean by “community.” And a definition of “community” that isn’t explicitly broad will end up reducing community to being defined as people.

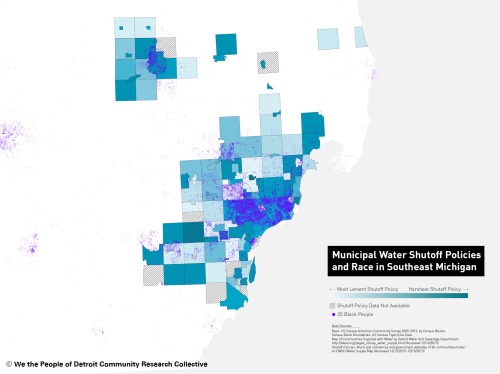

If we define community as a nexus of interdependent relationships, that is, those relationships that we are dependent on for thriving, then community certainly includes, but is not limited to, the human. In addition to the people we are connected to, knowingly or not, we are also clearly dependent on, among other things, the air we breathe, the water we drink and the soil we grow our food in. We don’t think we need to point out that currently our dominant culture monetizes even these “members” of our community in a way that obscures our dependence on them. Essentially, this monetization of our water, our soil, and the critters that depend on them serves to Otherize and erase. Our food, for instance, is dependent on worms, bees and bats. But the monetization of food creates a necessity of scale, which means worms are erased with the application of fertilizer. Bats are erased with the application of pesticides. The concrete world is erased by the imposition of the market and money as the primary value. And, because of the continuous necessity of human life as interdependent with this concrete world in the most fundamental of ways, the logic of this system leads ultimately to our own erasure.

Restorative Practices are a fairly new movement within schools and communities, but they are not new. We look at them as progressive, and they are in our times, but they are actually based on the traditions of the indigenous Maori of New Zealand. As practices they go back to what has worked within community for thousands of years. In this sense they are deeply conservative. And conservative really means “to conserve” those things that “work.” (We put this in quotes because in our times, what “works” is often reduced to that which is economically expedient.) The most “conservative” communities are always those indigenous to place. Their ways are the ways that necessarily “work” in accordance with place. If we are to live on what the Native Americans call Turtle Island and we have named America, we should probably look back to some of the traditions that have worked here for thousands of years. In fact, until relatively recently, most humans have necessarily acted with the awareness that we are always dependent upon the sources of our life that sustain us, the non human elements that make up our community. Chief Seattle famously put it this way:

“Man did not weave the web of life, he is merely a strand in it. Whatever he does to the web, he does to himself. All things share the same breath – the beast, the tree, the man… the air shares its spirit with all the life it supports.”

We used to recognize that all of the members of our community, human and non-human, are “sacred.” By this we don’t mean anything spiritual in a woo-woo way. We mean something much different, something very concrete, and, in the deepest sense, something very practical. Parker Palmer said that the sacred is, “That which is most worthy of respect.” People, specific, concrete, living, breathing people, are most worthy of respect. The children we work with are most worthy of respect. The air we breathe is most worthy of respect. The water we drink is most worthy of respect. Anything that we are interconnected with is necessarily most worthy of respect. In the past, we had languages that recognized the value of all of our relationships, and that helped with the negotiation of these relationships. The language of “achievement” and “standardization” function to override these older languages, thus erasing our interdependence with each other and the natural world. What if all of the time that kids and teachers took studying or taking tests was spent outside, observing, caring for, learning with and from all of those in our community, both human and other natural beings? Such as these are sacred. And one way or another, we always pay the cost for any disrespect. We always pay the price for treating the sacred as profane, for making a commodity of anything that is sacred. How to live and work with this awareness? How to teach with this awareness?

Again, how to include the voices of the ignored?

Place Based Education begins to offer some answers.

The Flipped Classroom: Going Back Home for the New Globalization

By now we are all aware of the technocratic answer that “flipped classrooms” offer to using technology as a means of revolutionizing the delivery of instruction. This form “flipping’ the classroom uses technology to puts the lecture portion of a class online as homework, and allows the instructor to work directly with students during class time as they practice the lecture lesson, thus “flipping’ the lecture and homework. One of the problems with “flipped classrooms” used in this way is that it doesn’t necessarily reimagine the “delivery of instruction,” nor does it offer a critique of this notion of “instruction” that needs to be “delivered.” “Delivery of instruction” maintains a comfortable stance well within the paradigms of hierarchical systems. “Instruction” is the means instructors (those in power) use to “deliver” content to students who, within this system, remain passive recipients of content delivered to them. This instruction is “managed” through technology.

We propose a much deeper means of “flipping the classroom.” One that actually reshapes the way we imagine education at its root, one that reimagines the role of “teacher” and “student.” One that necessarily invites and ground students in the context of relationships that are fundamental to sustainability and to the rebuilding of community.

Place Based Education flips the classroom by grounding students in the places in which they live their lives. It explores science from the perspective of the earth. It grounds them in social studies by grounding them in the relationships of their community. It grounds them in reading and writing by beginning with and honoring the languages of their families, friends and community. It honors art in all of its expressions as a means of sharing local culture. These allow for way a into education that honors students, honors tradition and honors place as concrete expressions of concrete relationships that students are necessarily involved in.

For example, we have been thinking a lot of “globalism.” If the purpose of a global curriculum is to learn how to cooperate and communicate with those different from you, then one’s place can serve as a global classroom. Try this simple exercise: Without paying attention to power relationships or “do not enter signs,” if you were to walk for 5 miles (most often doesn’t take that much), you might come across wealthy areas, trailer parks, immigrant communities, living landscapes of all kinds. The “global” is here in the local, it is just that systems developed by others have gotten in the way of us developing relationships. And because these systems actively work to erase parts of our communities, people for whom the systems are structured to privilege don’t even notice. Growing up in NYC, for example, Ethan never went above 96 street. He was taught that it was dangerous. Later in life, as a teacher in Spanish Harlem on 105th Street, he learned from the young people he worked with that they almost never went below 96th street. They were taught that they did not belong there. There was an invisible border there. Bill grew up in a farming community, but had never walked through a corn field until forced to do so when he got stuck hitchhiking home from high school football practice. Walking through this corn field, he realized that this space was alive in ways he was previously unable to imagine. Removing these borders that serve to Otherize whole aspects of our own communities reintroduces us to the global right where we are.

Place Based Education situates students within their place. This context of place, when it is made visible, provides the opportunity for learning to speak the language of interdependence, for making visible once again a world that we are in relationship with, a world that we are. It offers a form of resistance to the dominant culture that is unconsciously set on suicide. It offers a direction for re-embedding ourselves within our communities for the sake of our future and our world. It recognizes that this concrete world that we are tangled up with matters.

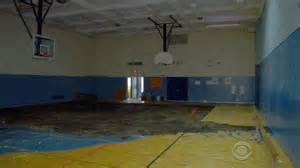

Let me be clear. Detroit schools are under the gun.It’s not their fault- they are trying to survive.

Let me be clear. Detroit schools are under the gun.It’s not their fault- they are trying to survive.